A Kindling of the Heart

How do we see into the heart of a child?

Do we watch children walk out of our atria and wonder, “Has any of my work touched their understanding, helped them understand our faith, or grown their knowledge of God?”

Of course, this very question reveals our perspective is wrong. We know as catechists that it is not we who are the teachers in our atria. Christ is the only teacher there. As set forth in the 32 Characteristics of the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd, the fruits of the child’s experience in the atrium belong to Christ; they are not ours. Our work is simply to live in faith, to be an unprofitable servant, to prepare the environment for the child, to introduce the child to a material made ready for his use, and then to observe and record her work.

Why do we observe and record the child’s work? We do so first, because this is the way we determine what material a child has mastered and which materials to present next to her in order to invite her to contemplate more fully the mysteries of faith.

However, returning to my first question, observation and documentation are also the most effective tools given us for seeing into the depths of a child’s heart.

Observation and documentation of children’s artwork over the scope of a year allowed me for instance to see into the heart of a kindergarten child, Piper, in a Level 1 atrium. Gregarious and fun-loving, Piper began her third year in a Catechesis of the Good Shepherd atrium in August, and she gravitated naturally to the center of her class’ social sphere. Upon entering the room each week, her crowd moved to the art shelf, chatting and choosing colored pencils carefully, examining them for length, sharpness, and color. Once satisfied with their tools, they settled together, still gabbing, at the long table and drew together: rainbows, flowers, cards for their mothers, and, occasionally, crosses or nativities. Using my iPhone and an app called ArtKive, I surreptitiously snapped and archived photos of their artwork. In the calm after the children left, I studied their drawings in order to answer my constant question: could I see what was going on in the hearts of the children?

Over time patterns began to emerge. In Piper’s artwork in particular her response to her true Teacher was revealed as one of longing, of joy, and of great love. A study of her drawings made over the course of the year revealed a profound interest and joy in the sacrament of baptism.

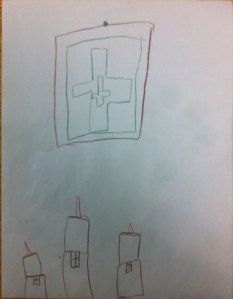

According to my observation notes for the year, it was November 11 that Piper first pinned to the prayer wall in our room a drawing she had made. To those familiar with our atrium, it was clear that her drawing represented the atrium’s baptism corner. The paschal candle, marked with a red cross, stood tall in the center of her drawing, and just as it did in our baptism area, a cross hung above it. In both her drawing and in our baptism corner, the paschal candle was flanked by two smaller candles representative of the baptismal candles given to a catechumen at his or her baptism. I found it interesting that Piper had drawn all three of the candles in her drawing with crosses and with flames. While a true baptismal candle often is marked with a cross, our small candles in the atrium are simply white vigil candles. Were these crosses based upon her own observation of baptismal candles given out at a baptism in her church? Or was she expressing a personal understanding of flaming baptismal candles as a sign of the light of the Risen Christ shared with a newly baptized individual? My observation notes for the day included these questions about her work: “Is this an exercise in artistic representation of our space, or is it theological drawing expressing her understanding and interest in baptism? Keep a watch and be prepared to speak to her parents.”

A few weeks later, on December 2, Piper left her group at the table and asked me to light the paschal candle at the baptism corner. Afterwards, as I later lit the baptismal candle for her from the Christ candle, I reminded her that when Jesus rose, he brought a risen light so strong that death could not extinguish it. I wondered with her what that light must be like and what it would be like to become filled with this light. Piper did not answer, and I did not press her. A child’s silence is often the outward sign of deep contemplation in the inner being of the child’s heart, a contemplation for which the child does not have words. So, I moved away and kept watch from a distance, leaving her to watch her small candle flame in silence. She sat there in the baptism corner watching the flame of her candle for the majority of the period before returning to the art shelf. I did not get the opportunity to see what her art expressed that day. How I wish that I had!

The next week the children explored the scriptures of the Annunciation from Luke. Following the discussion, Piper created a picture of a female, dressed in blue, above which she had written the word “God.” Because I was near, I heard her explain to her neighbor at the table that the figure was Mary. This did not surprise me. Mary had been a subject of interest in the presentation just before, and the Mary of our Annunciation work is a soft, blue felt. It was easy to see the iconography.

The next week the children explored the scriptures of the Annunciation from Luke. Following the discussion, Piper created a picture of a female, dressed in blue, above which she had written the word “God.” Because I was near, I heard her explain to her neighbor at the table that the figure was Mary. This did not surprise me. Mary had been a subject of interest in the presentation just before, and the Mary of our Annunciation work is a soft, blue felt. It was easy to see the iconography.

What was most interesting was Piper’s casual comment about the drawing to her neighbor: “God came into Mary from above, like when we are baptized.” The connection she made between incarnation and baptism, and her linking of the role of God the Holy Spirit overshadowing Mary at the incarnation and ourselves at baptism in a similar manner fascinated me. Truly, children have a way to see to the heart of Christian mystery in a manner which strips away the accumulations of politics and theology which divides us as adults. It took a very long time for the representatives of the various Christian denominations to the World Council of Churches conference in Lima to come to such a clarity of understanding about the shared doctrine of baptism. The Lima Document , finally adopted in 1982, states that “In God’s work of salvation, the paschal mystery of Christ’s death and resurrection is inseparably linked with the pentecostal gift of the Holy Spirit,” and it goes further to define the role of the Holy Spirit in baptism as marking a seal within the baptized which anoints the baptized as the son or daughter of God.

God bestows upon all baptized persons the anointing and the promise of the Holy Spirit, marks them with a seal and implants in their hearts the first instalment of their inheritance as sons and daughters of God. The Holy Spirit nurtures the life of faith in their hearts until the final deliverance when they will enter into its full possession, to the praise of the glory of God (II Cor. 1:21—22; Eph. 1:13-14). (Baptism, Eucharist, and Ministry. Geneva: World Council of Churches, 1982. 10. Web.)

This action of the Holy Spirit who, in descending, marks one as the inheritor, the child of God, is made manifest both in our ecumenical understanding of baptism and in the texts of incarnation which Piper was illustrating:

The angel said to her, ‘Do not be afraid, Mary, for you have found favour with God. And now, you will conceive in your womb and bear a son, and you will name him Jesus. He will be great, and will be called the Son of the Most High, and the Lord God will give to him the throne of his ancestor David. He will reign over the house of Jacob for ever, and of his kingdom there will be no end.’ Mary said to the angel, ‘How can this be, since I am a virgin? The angel said to her, ‘The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you; therefore the child to be born will be holy; he will be called Son of God. (Luke 1:30-35)

Clearly, Piper’s drawing of the incarnation is not simply a response to the infancy narrative, but an understanding that in baptism we become as Christ, marked as an inheritor of God’s kingdom and named by God as his own child. This was a further exploration of the sacrament of baptism, a continuation of her work from the week before. Perhaps her initial drawing had not been simply a still-life of a part of our room; perhaps it had been truly a theological exploration of the articles of baptism. With this second drawing and with her statement to her classmate, Piper revealed distinctly that she was engaging in mystagogy, a meditation upon the mystery of our sacrament. I made a note in my observation folder to keep a close eye on her artwork in the weeks ahead.

On February 24 I glimpsed Piper again at work with the art materials following a presentation on the parable of the hidden treasure from Matthew 13.

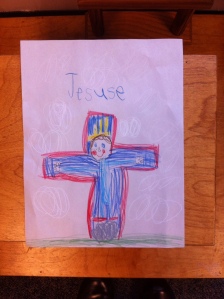

Piper first drew three yellow rectangles in ascending size on her paper; each rectangle she marked with a green/blue cross. At this point she seemed to be drawing again the baptismal candles from her very first picture. However, her next additions to the picture expanded the mystagogy of the baptismal candles. She drew a figure of a smiling man in blue, his head resting on the rectangles, and then she surrounded these elements with a red outline of a cross. Called to assist another child at the prayer table, I did not see the order in which the remaining elements were added. I heard her explain the swirls of white which surrounded the cross though. “God’s breath” she told her friend as I was passing the art table on the way to light the candles at the altar work for another child. When I walked back past, I saw that she had labeled the figure “Jesuse” and had added a gray circle at the base of the figure’s feet. I wondered about the significance of the gray circle, about God’s breath surrounding the cross, about the yellow bars above the figure’s head. I have seen similar circles in children’s drawings before. They appear frequently as the stone in images of the resurrection. Was this a moment in which Christ was caught between the cross and the tomb? Or between his death and resurrection? Why the smile? Why the bars of yellow? The ‘breath of God’ was a clue: Piper seemed to have drawn an image of the mystery of faith, (“Christ has died, Christ is risen, Christ will come again.”), a unification of the crucifixion, the tomb, the resurrection into new life. Here is a joyful Christ into whom God has breathed his ruach –again the Holy Spirit appears! — and from whom bursts forth a new and vibrant light of risen life. I couldn’t help but feel that the expression of this joyful Christ was one that invited the viewer to engage with him in this transformative, Spirit enlivened experience.

Piper first drew three yellow rectangles in ascending size on her paper; each rectangle she marked with a green/blue cross. At this point she seemed to be drawing again the baptismal candles from her very first picture. However, her next additions to the picture expanded the mystagogy of the baptismal candles. She drew a figure of a smiling man in blue, his head resting on the rectangles, and then she surrounded these elements with a red outline of a cross. Called to assist another child at the prayer table, I did not see the order in which the remaining elements were added. I heard her explain the swirls of white which surrounded the cross though. “God’s breath” she told her friend as I was passing the art table on the way to light the candles at the altar work for another child. When I walked back past, I saw that she had labeled the figure “Jesuse” and had added a gray circle at the base of the figure’s feet. I wondered about the significance of the gray circle, about God’s breath surrounding the cross, about the yellow bars above the figure’s head. I have seen similar circles in children’s drawings before. They appear frequently as the stone in images of the resurrection. Was this a moment in which Christ was caught between the cross and the tomb? Or between his death and resurrection? Why the smile? Why the bars of yellow? The ‘breath of God’ was a clue: Piper seemed to have drawn an image of the mystery of faith, (“Christ has died, Christ is risen, Christ will come again.”), a unification of the crucifixion, the tomb, the resurrection into new life. Here is a joyful Christ into whom God has breathed his ruach –again the Holy Spirit appears! — and from whom bursts forth a new and vibrant light of risen life. I couldn’t help but feel that the expression of this joyful Christ was one that invited the viewer to engage with him in this transformative, Spirit enlivened experience.

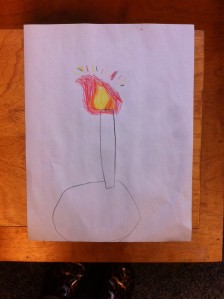

From this point on, Piper drew an avalanche of baptismal imageries. On March 3 following a presentation on the first few verses of Psalm 23 and a discussion of the verse “even though I walk through the darkest valley I am not afraid for you are with me,” Piper worked with the Eucharistic presence materials. Then sitting down to the art  table she requested an orange pencil and went to work with great fervor and energy to depict a flame. The few lines which suggest a candle (a rudimentary rectangle and circle) appear simply place holders on the page and were added in the hurried few seconds as she cleaned up to leave the room. Unlike her earlier depictions of candles, there is not a cross or other external identifiers of the candle as a sign of Christ. Instead, her focus is purely on the flame, a symbol throughout scripture and Christian art as a sign of the Holy Spirit.

table she requested an orange pencil and went to work with great fervor and energy to depict a flame. The few lines which suggest a candle (a rudimentary rectangle and circle) appear simply place holders on the page and were added in the hurried few seconds as she cleaned up to leave the room. Unlike her earlier depictions of candles, there is not a cross or other external identifiers of the candle as a sign of Christ. Instead, her focus is purely on the flame, a symbol throughout scripture and Christian art as a sign of the Holy Spirit.

I felt confident that Piper’s intentional drawing of the flame was an expression of her experience with the Holy Spirit, and yet I was left with a question. Had she experienced the Holy Spirit in her contemplation of baptism? Piper’s flame of the Holy Spirit was clearly set in the context of a candle, and this series of drawings began with one which had as its subject the candles of the baptismal corner. Here, it was as if those small flames and as if the rectangular golden bars of her drawing of Christ’s death and resurrection had flamed into life. But is this the Paschal candle or the baptismal candle? Is this an image of Christ aglow with the Risen Light ignited by the Holy Spirit, or is it Piper filled with the light of the Risen Christ in baptism? Or is it simply God, a mystic flame, as Moses encountered him in the burning bush?

Note that the grey circle of her prior drawing of the crucifixion is still present at the foot of the candle. This gray circle seems to me to be evocative of the gray circle at the foot of Christ in her crucifixion drawing. In this case it seem to indicate that the candle IS the Risen Christ aflame with the Holy Spirit and that the rectangles of light above Christ’s head in that drawing have become in this one rays of light protruding from the head, the flame of the Light of God. But could I be sure? Could this representation of a candle truly be an image of the risen Christ illuminated by the Holy Spirit, of the light of the risen Christ given to us as a gift in baptism?

In discussion with her father about this drawing of the candle, he suggested to me at the time that this circle could simply be the cup in which the vigil candle was held. Without the context of her prior drawings and my observation of her work I would not have had support for my sense that this flame is more than a pictorial representation of an object; my sense is that this is an icon of her mystic experience with God.

On March 24, following a presentation with the class of the gesture of the washing of the hands from the Eucharist in which the words of Psalm 51 were added (“Create in me a clean heart, O God”), Piper set to work with the art materials. Once again she dew a candle with a large flame. This time though she provided additional clues for our interpretation. Above the candle she wrote “I love God!” Beside it she drew a red cross with a figure in black upon it. The candle is approximately twice the size of the cross. The connection of the cross to the candle reveals that she does synthesize the death of Christ with the light of the Risen Christ in baptism, and the size ratio of the candle to the cross reveals her understanding of the enormity of the Risen Light. Her words above the candle reveal a response of great love to this gift of Risen Light. Whereas in her drawing of the Annunciation the word “God” simply represented a descent of the Divine being, now the candle itself is all humanity – Mary, Jesus, Piper — within whom the Holy Spirit is made manifest and who anoints and nurtures a life of faith, finally setting free praise of God. Like Simeon before her, Piper is singing about the light to enlighten the nations.

Now, Piper has not read the Lima Document, created after much discussion and struggle by representatives of different Christian denominations to clarify points of doctrine in baptism are shared by all Christians. No, her clear and pure faith simply puts forth in her child’s drawing what years of adult debate concluded in that hard won consensus of faith.

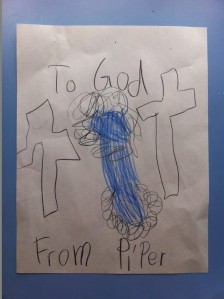

Piper wasn’t finished. On April 14, following contemplation of the Holy Week narratives through use of the concrete model of the City of Jerusalem, Piper again chose the art materials. She began by drawing a great blue swath in the center of her paper, and then she sat back and looked at it. To me it looked at first as though she were beginning again to draw a Mary like that of her earlier annunciation drawing. This similarity was underscored when she wrote the name “God” above the blue swath as she had in that earlier drawing. Then she wrote “Piper” beneath it. Was this a return to the idea of the earlier picture, that just as God’s Spirit entered into Mary, God’s Spirit entered into us in baptism, I wondered?

She then drew in black a cross to the left and a cross to the right. She went back to the art shelf and looked for a white pencil. Not finding one, she drew with her black pencil the looping shapes she had made on the crucifixion earlier, but this time only at the top and bottom of the blue swath. Were these also God’s breath, God’s spirit? Apparently finished with her drawing, she pinned it to the board.

She then drew in black a cross to the left and a cross to the right. She went back to the art shelf and looked for a white pencil. Not finding one, she drew with her black pencil the looping shapes she had made on the crucifixion earlier, but this time only at the top and bottom of the blue swath. Were these also God’s breath, God’s spirit? Apparently finished with her drawing, she pinned it to the board.

She wandered a bit (oh, why did I not write down to which works she wandered!) then went back, took down her drawing, and added the word “To” before “God” and “From” before Piper. With a sense of finality, she pinned the drawing to the board once more, and then went straight back to the art shelf.

There Piper took a paper, folded it in half to make a note card, and drew a large heart on the front of it. She again wrote “To God” and “From Piper” but this time she reversed the positions of the words on the top and bottom of the page.

There Piper took a paper, folded it in half to make a note card, and drew a large heart on the front of it. She again wrote “To God” and “From Piper” but this time she reversed the positions of the words on the top and bottom of the page.

Opening the fold, she drew a large heart shaped face on the right side. Curls on the top appear to be eyes while curls on the bottom appear to be feet. She added a curve (smile?) and two lines (nostrils). A symbol of God who is love? A symbol of Piper who loves God?  This card she brought as a gift to me (her first time ever to do this); when I asked if she wanted me to put it on the bulletin board, she just shook her head “no”, smiled, and went to put her pencils away.

This card she brought as a gift to me (her first time ever to do this); when I asked if she wanted me to put it on the bulletin board, she just shook her head “no”, smiled, and went to put her pencils away.

I’ve wondered about these last artworks. The blue swath is so similar to her first drawing of the annunciation. Is this an abstraction of humanity clothed as Mary? Or is it, with its black loops at top and bottom, an abundance of water, a waterfall? Was this water spilling from God to Piper? Was it both? And why the crosses?

The more I contemplated her work, the more I began to believe it included all of these elements. This was another expression of her growing awareness of the signs of baptism and the pouring of the consecrated water over the baptized. The outpouring of blue marked by the swirls of God’s ruach pours in abundance from the word “God” to “Piper,” and the blue is both the water and Piper/Mary experiencing the outpouring of God’s Holy Spirit. The placement of the water between the crosses captures the traditional imagery of the three crosses on Calvary, although here the waterfall takes the place of the cross of Christ. Filled with the Holy Spirit in the outpouring of the baptismal waters, Piper/Mary/Humanity is clothed as Christ. My notes for the day show that other children around her at the time she drew this image were themselves drawing images of a hill surmounted by three crosses. Piper was, unlike them, synthesizing the death of Christ, the descent of the Holy Spirit, and the Annunciation with the gestures and signs of baptism. Again, all of these meanings are present in the Lima Document’s discussion of the role of water in Baptism in which Christ’s death and resurrection, the enlightenment of the baptized by Christ, the renewal by the Holy Spirit, and the flood of cleansing water are lifted up:

The New Testament scriptures and the liturgy of the Church unfold the meaning of baptism in various images which express the riches of Christ and the gifts of his salvation. These images are some- times linked with the symbolic uses of water in the Old Testament. Baptism is participation in Christ’s death and resurrection (Rom. 6:3–5; Col. 2:12); a washing away of sin (I Cor. 6:11); a new birth (John3:5); an enlightenment by Christ (Eph. 5:14); a re- clothing in Christ (Gal. 3:27); a renewal by the Spirit(Titus 3:5); the experience of salvation from the flood(I Peter 3:20–21); an exodus from bondage (I Cor. 10:1–2) and a liberation into a new humanity in which barriers of division whether of sex or race or social status are transcended (Gal. 3:27-28; I Cor. 12:13). The images are many but the reality is one. (Baptism, Eucharist, and Ministry. Geneva: World Council of Churches, 1982. 9. Web)

So, Piper — a five year old in a preschool atrium — is meditating upon and illustrating a point of confluence of Christian doctrine from diverse denominations which was set forth by the authors of the Lima Document in this way:

In the celebration of baptism the symbolic dimension of water should be taken seriously and not minimalized. The act of immersion can vividly express the reality that in baptism the Christian participates in the death, burial and resurrection of Christ. (Baptism, Eucharist, and Ministry. Geneva: World Council of Churches, 1982. 14. Web)

And what of her final gift to me? The “love note” is, I believe, an expression again of great joy and love in response to what she realizes is the great gift of baptism, a gift from God to Piper which she has discovered in the environment she knows I have prepared for her in our school atrium. Piper, the social butterfly who chats about pink bows and kittens and birthday parties at the art table with her friends, has been contemplating and celebrating the great gifts of baptism.

Could I have missed what her heart was contemplating while she was gathered at the art shelf, the social center of the atrium? Oh, yes! If I had not kept snap shots of Piper’s artwork or notations in a journal about her work and her comments, the trail of her mystagogy would have been indecipherable. Any single drawing, seen on its own in isolation, would have hidden the greater meaning it revealed only when placed in the context of her work over many months. How many such kindlings of the Spirit in the heart of a child have I missed in the past simply because I was not observing, not documenting, the work of the child in the atrium.

To return to our initial question then, how can we see into the heart of the child, see if the environment we prepare or the presentations we offer open up the child’s heart to God’s loving presence? We cannot discern the workings of a child’s heart through our questions or our examinations. We can only perceive it if we live in the spirit of faithful observation. The unfolding plan of God is discernible only to those who wait and watch with hope.

.

The Prayer

Today I remember another day, a day thirteen years ago when I sat near the prayer table in our school atrium. Around me were gathered fifteen third graders who were waiting for me to talk about what had happened the day before, to offer them God’s explanation of the images they had seen playing in continuous loop on their television screens at home: planes crashing into the twin towers; fiery, collapsing buildings; ash strewn streets filled with crying people.

My heart was a desert. My tongue sered dry of words.

I escaped to the lesson plan I had prepared the week before, the week before we knew the terror, uncertainty, and grief that the day before had brought.

“We are studying the Maxims today,” I mumbled, refusing to meet their eyes. “A maxim is a moral commandment. These are commandments Jesus gave us.”

I rolled out the mat. Placed the ark containing the scriptures on the mat. Kept my eyes averted.

“Let’s take them out and see what we find.”

I took the set of tablets from the ark and shuffled them, face down, spread them in a fan on the floor, and asked three children to pick one tablet each and read it to themselves silently. Then while these three sat back to turn over their chosen tablets and discover the scripture written upon them, I scooped up the remaining tablets and returned them to the cabinet.

While I was still occupied, my eyes averted, I heard the first child begin to read the tablet he had chosen randomly from the stack.

“Pray for those who persecute you,” he read.

The stillness and silence in the room seemed suddenly expectant, as though an invisible presence waited amongst us.

I looked up and saw another child looking at me, her eyes asking if she too should read her tablet aloud. I nodded to her.

“Love your enemies,” she read.

The silence felt like a great weight, and I felt an unreasonable anger well up in me. No, these were not the words I wanted to hear. I was afraid of the friends I might have lost; I was grieving those I knew I had lost. While grappling with these emotions I heard the last child begin:

“I give you a new commandment. Love one another as I have loved you.”

What could this mean? How could I approach these texts on this day, this September 12th, this day when the world had changed around us forever?

The children asked if we could light more candles on the prayer table, and so we did. They asked if we could pass the prayer cross around and pray together, and we did. Prayers for comfort, prayers for the injured, prayers for the responders were all offered.

The class of seven year olds left; the next class of seven year olds entered. Again, I introduced the term “maxim.” Again, I shuffled the tablets and placed them face down in a fan on the floor. Again three children picked from amongst the fifteen tablets a few at random.

The first child read, “Love your enemies.”

The second child read, “Pray for those who persecute you.”

The third child read, “I give you a new commandment; love one another as I have loved you.”

Again, I sat speechless, struggling against these words that hammered me like stone tablets.

“It’s like Jesus,” said a small red head with a large bow. “He told God to forgive the people who hurt him on the cross.”

The children all nodded.

Then one young boy who had been sitting in contemplation, rereading over and over the tablets which had by now been placed on a mat before the prayer table, looked up.

“Ms. Kay, isn’t God everywhere?”

“Yes,” I answered.

“Remember how you told us that there are two kinds of time? That our time goes only one direction, and we can’t go back, but that for God all times are one time?”

“Yes,” I answered.

“Then, Ms. Kay, can we pray for God to be with the people who flew those planes, to help them not be so sad and angry? If we pray for them, and if God is in our time and their time too, then perhaps God will give our love to them and will help them. Maybe then no one will be sad.”

It was not what I had wanted to pray. What I had been unconsciously praying all day was a simpler, harsher prayer: “Give them, Lord, what they deserve.” Yet in the expectant silence, in the midst of that invisible presence, and with the eyes of fifteen trusting children upon me, I knew my unspoken prayer took on a new meaning. Give them, give them all, the children in the room, the lost in the two towers, the hijackers, the mighty in their places, and the powerless in their refugee camps, give them all what they truly deserve: a love which knows no limits, a time when no one will be sad, a future when “nation shall not lift up arms against nation.” This was a prayer which could fill the room with light, peace, comfort, and meaning.

Yes, this was a prayer we could offer. I knew on that day, and I believe it still, that there will come a day when no one will hurt or destroy in all this holy creation, when “they shall beat their swords into pruning hooks and their spears into plowshares.” (Isaiah 2:4) I long for that time proclaimed in Isaiah when all creation will be sustained in harmony, and nothing living will inflict pain on any other living creature simply because “the earth will be as full of the knowledge of the LORD as the waters cover the sea.” (Isaiah 11) Believing in the power of prayer to change the hearts of all men, in all times and all circumstances and spiritual conditions, we bowed our heads and prayed.

And prayer indeed worked miracles. In one angry heart, in a small school in Texas, vengeance and suffering was soothed through God’s grace to become, if not not sad, at least at peace . . . and trusting in a day to come.

The Atrium and Nature: Sorting through the Sorting Materials

The mother and child peeked into the atrium as I was tidying away the materials left from the kindergarten group that had just left. Peering up over her glasses, the four year old bounced up on her toes, making the large bow on her red hair tremble and slip further sideways.

“Miss Kay, I want to show my mom the book,” she whispered.

“Of course,” I replied. The little girl grabbed her mother’s hand and tugged her towards the windows at the back of the room to the nature table. There on a square of soft felt rested the magnifying glass, an amethyst geode, a chunk of citrine, and a pyrite sun still embeded in its slate. Next to the specimans lay a pictorial guide to rocks and minerals.

Eagerly the small child opened the book, located the images which matched the objects on the table, then picking up the magnifying glass and chattering excitedly about the minerals, she urged her mother to examine the specimans with her.

Later, as the mother and daughter left the room, the mother thanked me.

“She just loves the objects in your room,” she said. “For the last three weeks, all I’ve heard about is “The Book.” I had no idea what she was talking about, but I’ve promised we will find one for her. We’ve had to start collecting all kinds of rocks on every one of our walks; thank you for helping her really see the world around her.”

I was very grateful for her appreciation. I’m often self-conscious about my tendency toward natural history collections. A spring time walk with my husband will often bring us both home with hands full of objects I’ve picked up from the sidewalks and grass lawns of our neighborhood. At conferences I’m known to spend my breaks scanning the exterior surroundings for seed pods or lichens. Long after a colleague and I took an accreditation visit together to a distant school, he still teases me for the handfuls of bur oak acorns I celebrated finding there.

Yet they do not see what I see in my atrium every day. I’ve had students look at the perfect cones of beatiful blue robins’ eggs and become angry because “the candy has already been eaten” from them; been afraid to touch the selenite roses because “rocks are dirty”; ask how I painted the stripes on the sea urchin tests.

Yet they do not see what I see in my atrium every day. I’ve had students look at the perfect cones of beatiful blue robins’ eggs and become angry because “the candy has already been eaten” from them; been afraid to touch the selenite roses because “rocks are dirty”; ask how I painted the stripes on the sea urchin tests.

I’ll never forget the day a child asked what the maple wings were which I’d found on my walk the night before. When I showed him how it spun and spiraled down after being tossed in the air, the contagion of excitement in the room was such that we had to leave the atrium and go outside to spend the rest of the class with every child throwing the seeds upward and running to catch them as they floated, spinning earthward. Imagine growing up surrounded by such a simple thing — a maple wing — and never knowing that it was designed to fly! Imagine not knowing that a robin’s egg contained a baby bird, not Easter candy, or that sea urchin tests come in a glorious diversity of colored stripes dependent upon the unique species into which their Maker made them.

A primary goal of Montessori education and of the children’s work in a Catechesis of the Good Shepherd atrium is the orientation of the child to the reality in which they live. Such orientation to the beauty and generosity of the creation around them is the goal of the nature table in a Montessori room. A nature table — by providing a changing variety of natural objects in a space in which children are encouraged to examine them and in which children are given time to enter into meditative contemplation of them — assists children in falling in love with exploration of the natural world. It also invites the children into wonder over the creation as a great treasure given them by the Creator, to see the history of the kingdom of God as a history of God creating gifts for those whom God loves.

A primary goal of Montessori education and of the children’s work in a Catechesis of the Good Shepherd atrium is the orientation of the child to the reality in which they live. Such orientation to the beauty and generosity of the creation around them is the goal of the nature table in a Montessori room. A nature table — by providing a changing variety of natural objects in a space in which children are encouraged to examine them and in which children are given time to enter into meditative contemplation of them — assists children in falling in love with exploration of the natural world. It also invites the children into wonder over the creation as a great treasure given them by the Creator, to see the history of the kingdom of God as a history of God creating gifts for those whom God loves.

More than at any time in history, our children need these introductions to the created order. In 2005 Richard Louv first published his book, The Last Child in the Woods, and coined the term “nature deficit disorder” to diagnose a generation of children who are growing up without unstructured experiences in the natural environment. Louv argued that the human cost of “alienation from nature” was measured in “diminished use of the senses, attention difficulties and higher rates of physical and emotional illnesses”. In 2011 Great Britain’s National Trust published a Natural Childhood report which suggests that “UK children are losing contact with nature at a ‘dramatic’ rate and their health and education are suffering.” http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-17495032

The Natural Childhood study and Louv’s book identify consequences of alienating children from nature. Impaired abilities to learn from experience, under-developed traits of compassion and stewardship, obesity, decreased mental health and happiness are just a few of the results of nature deficit highlighted.

Exposure to nature however can rapidly reverse all of these. Studies have shown that ADHD symptoms improve when children are exposed to natural environments and that obesity drops and joy increases in children who are encouraged to enjoy unstructured, outdoor activities. In the Natural Childhood study, a surprising discovery was that children reported that their happiness depended more upon having things to do outside than in having more technological devices.

Are our schools meeting these needs of the children for nature? I recently spoke with a friend at another school who had searched her teacher’s workroom for natural materials to include in her Level 1 atrium sorting work. Common to all pre-school classrooms now, sorting works were introduced in Maria Montessori’s Casa dei Bambini. Comprised of a series of objects — say acorns, walnuts, and chestnuts clustered in a bowl — the work develops a child’s ability to observe and categorize objects by their characteristics. Because my friend, like me, liked to change the objects in the sorting work on a regular basis to invite interest and promote wonder, she had searched the workroom for something new to add to the work in the atrium.

She had searched to no avail. Oh, yes, she shared, if she had wanted to incorporate fluffy pompoms in varying sizes or colors or rubber erasers shaped like bunnies, eggs, or snowmen, such bits and pieces would have been plentiful. But she was searching for materials that would draw the children into wonder about the world around them, natural items which might inspire a response of love and stewardship for the abundant gifts of the creation. Plastics, Asian rubber toys, and colorful mass produced craft items abounded in the workroom, but nary a natural object was to be found.

Her futile search of the workroom revealed how nearly our contemporary environments often alienate our children from the created order around them. At home and at school we too often immerse our children with man-made objects in order to entertain them, and we find that this creates within them a craving for ever more, ever newer toys which lose value almost at the moment of their possession. By doing so we end up divorcing them from the reality of the world in which they live, depriving them of the joy of existing within endless abundance. This deprivation deviates a child’s natural development, his vital exigency for exploration, and, in addition to the consequences mentioned above, forces a child’s mind to find pleasure in fantasy rather than satisfaction in imagination.

What is the difference? Fantasy views the creation as incomplete and seeks to fill it with creatures which never existed. Imagination in comparison draws the child into wonder at the endless abundance of a creation so filled with miracles that the child encountering it is pulled ever deeper into its exploration. Or as Stephen Moss, the author of the Natural Childhood report, has said, “This is about changing the way children grow up and see the world. The natural world doesn’t come with an instruction leaflet, so it teaches you to use your creative imagination.”

So what are some readily accessible, natural materials for the sorting work in our atria? Our everyday environment presents a diversity and abundance of natural objects readily available for us.

The grocery store is a treasure house of sensory experiences from nature: whole cloves, cinnamon sticks, anise stars, and nutmegs are examples found on just one aisle.  On nature walks in my urban neighborhood I have picked up acorns of different species of oaks; cones from junipers, pines, and cedars; seeds balls of sycamore and poplar trees; the halves of robin, cardinal, sparrow and other bird eggs; a diversity of feathers; autumn leaves from oaks, maples, and Chinese pistache trees;and buds of hollyhocks, roses, and daisies from my own garden. A trip to San Francisco allowed me to bring back a tupperware container filled with eucalyptus nuts and their heady fragrance. On vacations by the sea my beach walks have yielded sea shells of endless diversity, shark’s teeth in sizes from less than a millimeter to as large as my palm, miniscule sand dollars, bits of coral, and even tiny horseshoe crab exoskeletons. My local farmers’ market brings a rainbow of organic heirloom seeds in varying sizes and shapes (care should be taken to ensure that seeds provided in a sorting work are non-toxic and free of pesticides and herbicides). Trips to science museums and mineral galleries have unearthed simple fossils such as orthoceras, ammonites, coprolites, and Green River formation fish as well as beautiful points of amethyst, citrine, flourite, and specimans of copper, pyrite, turquoise, optical calcite, selenite balls, and others minerals too numerous to mention. For all of these mineral specimans, I have sought untumbled and unpolished stones so that children can hold the natural material in their hands and see it unchanged from the state in which it was created.

On nature walks in my urban neighborhood I have picked up acorns of different species of oaks; cones from junipers, pines, and cedars; seeds balls of sycamore and poplar trees; the halves of robin, cardinal, sparrow and other bird eggs; a diversity of feathers; autumn leaves from oaks, maples, and Chinese pistache trees;and buds of hollyhocks, roses, and daisies from my own garden. A trip to San Francisco allowed me to bring back a tupperware container filled with eucalyptus nuts and their heady fragrance. On vacations by the sea my beach walks have yielded sea shells of endless diversity, shark’s teeth in sizes from less than a millimeter to as large as my palm, miniscule sand dollars, bits of coral, and even tiny horseshoe crab exoskeletons. My local farmers’ market brings a rainbow of organic heirloom seeds in varying sizes and shapes (care should be taken to ensure that seeds provided in a sorting work are non-toxic and free of pesticides and herbicides). Trips to science museums and mineral galleries have unearthed simple fossils such as orthoceras, ammonites, coprolites, and Green River formation fish as well as beautiful points of amethyst, citrine, flourite, and specimans of copper, pyrite, turquoise, optical calcite, selenite balls, and others minerals too numerous to mention. For all of these mineral specimans, I have sought untumbled and unpolished stones so that children can hold the natural material in their hands and see it unchanged from the state in which it was created.

When presented with such objects, even in so simple a material as a sorting work, the world opens up to the child, and his attention is now gained by the abundant diversity of nature around him. Time seems to stop for the child who becomes fascinated by the light reflected back from the heart of a quartz crystal, who becomes wrapt in contemplation of the iridescence of a donkey’s ear abalone, who abandons himself to the scent of a cinnamon stick or wand of lavendar.

When presented with such objects, even in so simple a material as a sorting work, the world opens up to the child, and his attention is now gained by the abundant diversity of nature around him. Time seems to stop for the child who becomes fascinated by the light reflected back from the heart of a quartz crystal, who becomes wrapt in contemplation of the iridescence of a donkey’s ear abalone, who abandons himself to the scent of a cinnamon stick or wand of lavendar.

Awakened interests in natural history can be extended by providing larger specimans of the natural materials at a “museum table” complete with a magnifying glass or microscope for children to use in their explorations of the materials’ appearances and properties. Older children who have become adept at reading can return to these same materials again if provided with simple printed guides to minerals or shells which allow the child to identify and categorize these objects using more sophisticated elements of classification.

Awakened interests in natural history can be extended by providing larger specimans of the natural materials at a “museum table” complete with a magnifying glass or microscope for children to use in their explorations of the materials’ appearances and properties. Older children who have become adept at reading can return to these same materials again if provided with simple printed guides to minerals or shells which allow the child to identify and categorize these objects using more sophisticated elements of classification.

Does this emphasis on natural materials belong within a Catechesis of the Good Shepherd atrium? Absolutely. Much can be said about the place of natural objects from the creation in the spiritual and moral formation of children, and a future post will explore the relationship between wonder, enjoyment, prayer, and the moral response of stewardship.

Mystagogy of the Child

I was in a hurry, sweeping up items left unrestored by the children who had left the atrium. I was in such a hurry I nearly missed, nearly swept away the simple statement left behind at the gestures of the Eucharist table. There, in an act of mystagogy made visible, was the paper bread left over from a child’s enactment of the fraction. Was it an accident that it was left as a heart on the paten?

What goes on in the heart of a child as he or she works with the materials in the atrium? Just as we can only approach the great Eucharistic mystery itself through the signs of the liturgy – the epiclesis and offering, the fraction, the peace, the sharing of the one bread — so too we can only approach the great mystery of the child through the signs left behind for us to find: a drawing of a sheep, an echo of a child’s song at the altar work, a small paper heart left on the paten of the prepared gestures table.

Kneeling in front of this tiny, this momentous offering, I realized for the first time the overwhelming nature of the gift of the Eucharist: not a body, not a sacrifice, not just a gift, but an outpouring of love which flows to us like the river of life. This love I saw was not static, not simply waiting upon a plate. It was a movement of love from Christ towards the Father and towards me.

The discovery sent me, a library mouse, back to my books. Was this understanding of the Eucharist as a movement of love already there, and I had simply never noticed it before? And of course it was.

“Thus the presence that is appropriate and intelligible in the Eucharist is neither the presence of an idea in our minds . . . nor the presence of a uniquely sacred object on a table. It is the presence of an active Christ, moving in love not only toward the Father but towards us. The more we try to ‘immobilse’ Christ, either in heaven (so that all that happens in the Eucharist is in our minds) or in substantial presence on the altar (so that his action is virtually completed in simply being there under the sacramental forms), the less we understand of the dynamism of the sacrament, and of the transfiguring liberty of the risen Christ. For if we look first to Christ in the Eucharist as active, we can see how sacrifice and presence together make sense. The offering of the love of the Son in his incarnate life and bloody death is woven into the eternal life of the Trinity; when the crucified Son is raised from the dead, we understand that the cross is an abiding reality, an indestructible life and an inexhaustible gift. And the great mark of discipleship to the risen Christ is, as the New Testament has it, that we eat and drink with him after his resurrection: the love given to the Father is given to us who receive his hospitality.

(Rowan Williams, “Foreward”, The Mystery of the Eucharist in the Anglican Tradition)

But was I reading too much into this tiny paper heart left behind on the paten? I returned to my atrium notes, and of course, the pattern emerged.

“January 30, second grade, I found one of the coins from the Found Coin work left in the center of the sheepfold. Accident? It stands at the foot of the shepherd and the sheep are facing it in a circle.”

“February 7, second grade, A small paper heart left behind in the center of the sheepfold. It reminds me of the coin from last week. The shepherd is not present. It seems the sheep are positioned around it, facing it.”

“February 23, second grade. The table from the Eucharistic presence work was left on the gestures table. No other part of the materials from that work. It sat upon the lace cloth for the gestures work.”

Clearly, a single child had been cogitating each week upon the meaning of Christ’s presence in the Eucharist, moving from the concrete representation of the Good Shepherd who calls his sheep to be fed to the mystagogy of the Eucharistic gestures. No, the heart, I think, is not an accident, but another sign of the kingdom of God, a sign I nearly missed. Like the leaven in the parable, it is hard to see, growing, transforming, rising within the heart of the child.

Food for thought, indeed, this heart shaped bread.

A Valediction to Lost Camp

It came. Just two miles from my bedroom window, five irrigation wells brought their angry drone, like creditors seeking payment, to my sleepless ears.

It was the solitude of the ranch which had given me the balance to find my way graciously through troubled times. In the solitude — the very emptiness of passion and sound — I had found the gentleness with which to love even tiresome acquaintances. But then to east and west this solitude had disappeared.

How odd it is to think that even twenty-five miles from the nearest town, peace could be ruptured by the encroachment of humanity.

Leaving the bedroom those fifteen years ago to pace sleeplessly the kitchen floor, I was driven back to my living room — a den in the oldest, animal sense of the world — to find the emptiness of space that my soul craved. Outside the east kitchen window, the brilliant white strobe of a distant cell tower — erected two years before to bring us closer communication with other humans — made humanity a disturbing, rather than a comforting, presence.

I am no hater of mankind. I am in fact a sociable being, gregarious by nature, drawn to conversation and community gatherings. But I am also a lover of solitude, and like good companionship, emptiness is necessary for the well-being of my soul.

Once the eastern horizon had been a velvety blankness, washed-in broadly with opaque strokes of dusky watercolors. Before that darkness one sensed rather than saw the hills swell along the draw, and the silver tolling of each star rang a clear sanctus beautiful to my ears. Each winter, Orion had risen from those unseen hills to stalk antelope across our serene pastures. But that night the celestial hunter was wounded by the slash of light that pierced his shoulder, his hip, as he struggled to rise from the swelling ground.

I remain saddened by the memory of that intrusion, the javelin of white that pierced the heavens, the searing light which falsly revealed a seeming reality of flat landscape in constant repetition.

I had found that only in the silent, dim places could we sense our proper place amongst humanity, could we sense in the cosmos a being older than time can measure. So many other nights, standing upon the still earth there alone with only the stars for light, I could feel in my calves the throb left in the ground from footsteps of ceremonial dances there thousands of years ago, could feel the rumble of wagon wheels rolling across some distant edge of those grasslands, could know beneath it all a deep voice which spoke only to my heart and said “I AM”. I had discovered that only in such a place, a place empty of humanity, could we gain a true perspective of our place within the scope of human existence and hear the words of the voice of God.

The silent, empty places are disappearing, and I feared that night fifteen years ago that that lovely, desolate, Lost Camp of mine would slip past me and my children to someone who did not hear its silent voice.

One would have thought that owning twelve sections of land around you would provide adequate insulation from the erosion of the modern world. A truth we have to learn is that we are never the true owners of our own horizons.

Can it be plastic?

The opening week of school several practical life materials in the room were broken: a soap dish at the handwashing work, a small porcelain bowl in the spooning work, and a glass carafe in the equal pouring work. Normally I replace these in my room at my own expense, but this year I decided to fill in a purchase order and ask the school to pay for the replacements. As I left for the afternoon, I turned in the completed purchase order.

The next morning I found the form returned to my box with a sticky note attached; it read “Can these be plastic?”

This is a question I answer all the time about materials in a catechesis atrium. Catechesis, which is founded on the principles of Maria Montessori’s work with children, relies on a prepared environment which orients children to the reality of the world around them and which provides children with an opportunity to engage freely in real work related to that reality.

Plastic utensils leave a child without that desired orientation to reality. A child who is given unbreakable objects is deprived of the opportunity to develop fine motor skills, care of their environment, and respect and responsibility towards the objects of their environment. Plastic bowls which can be handled roughly seem indestructible and therefore unworthy of care. However, surround the child with real, breakable, even fragile materials, and the child learns many valuable things.

They learn the material properties of an object or material. They learn to hold the items with care. They learn the consequences of stewardship and lack of stewardship. Part of what a child learns in the CGS curriculum thanks to our Montessori foundation is how to hold a material with two hands, how to carry a tray level with two hands, how to pour with a glass pitcher, and so on. When we as adults model holding and using items with care, the child sees us and learns to do so as well. It is not necessary to say “This is breakable; carry it carefully”; a child seeing the adult being careful becomes careful herself.

“But what about breakage?”, I am often asked. Rejoice in breakage! A broken item is a learning experience, resulting in that set of materials being taken off the shelf. That is the consequence of the breakage – there is no reprimand, just the feeling that something must be taken away until it is repaired or a replacement can be found. Breakage, which we too often try to avoid, is a good thing which provides a lesson in careful handling that cannot be communicated simply through lecture or admonition. Breakage immediately teaches the material properties of glass or porcelain in a way that no amount of language can convey. Breakage also makes way for new learning experiences. It provides for instance the perfect opportunity to teach a child how to use a broom or carpet sweeper, skills which children love to practice.

Do many items get broken in an atrium? Surprisingly not. In thirteen years of being a catechist in a school setting I don’t remember anything being broken until five years ago and only four things since primarily all by the same group of children as they have moved through the school. This last week, the breakage caused by two second graders having difficulty sharing a work was a lesson for a whole room of children still learning to handle materials and each other with care. I couldn’t have said anything that would have provided such an explicit lesson of the need for discipline in our movements and our behavior toward one another. In fact, I didn’t need to say anything to drive home the point of self-control, because the students involved immediately saw the consequence of their mishandling of the materials and apologized to each other and to me. They then settled into some of the calmest work I have seen them undertake since my son came to school one day, his long hair brushed back behind his ears, and they thought Jesus had come to watch them. The second breakage of the week was simply a new PreK student who is still learning to follow instruction, to carry a tray level, and to bend his knees when placing a tray onto a shelf. Having been asked four times to clean up, he only rushed to do so when his teacher arrived at the door. His apology to me? “If I had cleaned up when you told me, I wouldn’t have dropped it.” So, that breakage taught its own lesson too without my needing to say a word.

I think the final and best lesson about breakage is always found in the adult’s response, “Don’t worry. Now we can learn how to use the dust pan and broom, and now you know how you have to carry the (broken object) next time. And remember, you are far more dear to me than any (broken object) could ever be.”

A last word about the use of porcelain and glass in the atrium. The materials in the atrium should be so beautiful that a child LONGS to work with them. Earthenware condiment bowls touched with a golden glaze that glimmers in the light and makes the objects inside seem to glow or a crystal clear goblet in which the water sparkles as the child pours, these attract the child to work in a way that no plastic bowl could. Just imagine the sound of ice tea being poured into a glass on a summer’s day, and you know how enticing the sensorial properties of glass can be.

It’s no wonder that Montessori supply companies refer to sets of glass carafes and porcelain bowls as “consumables”. When we think of them this way then the fear of using them and the shame of breaking them is replaced by care for the environment and a love of stewardship. A whole other blog post awaits on the lessons we can model for children on consumerism, the need for stewardship, and the multiplication of mindfulness through the subtraction of unnecessary, unbreakable possessions.

A Montessori Adult Practical Life Lab

In 2008 and 2009, the National Association hosted two weeklong workshops in the Montessori basis of CGS. The first was focused on the role of the adult, the second, which was held in Nashville, on the nature of the child. I was only able to attend the second one, but this workshop caused a paradigm shift for me and changed the entire way I live in the atria with the children.

In addition to panel presentations led by catechists and Montessori experts, challenging and informational readings, and group discussions, the second workshop also included a three hour experience in an Adult Practical Life Lab. Designed and set up by Sherri Mock of Houston and Marilee Quinn of Kansas, the lab was comprised of two areas: a children’s area set up as a Montessori practical life, art, and nomenclature space and an adult area with hands-on activities meant to deepen our understanding of Montessori methodology. We were individually greeted at the door to this space by Marilee and told that this room had been set up just for us as a gift and that we were invited to explore either as a child or as an adult. We could go back and forth between the areas within as we wanted. If we had any questions, we could quietly find Marilee or Sherri (who was seated in her “directress chair” at the other end of the room), either of whom would be waiting to assist us.

For two hours (a typical Montessori class period) we explored. Next to each material in the children’s area was an 8 ½ x 11 sheet mounted on colored construction paper; this sheet had a photo of the restored work and step by step instructions on how to do the work. Spooning, pouring, polishing, sculpting, making baptism booklets, walking the line, all sorts of activities were available to us. One of the points lifted up was the need to provide a complete cycle of work for the child, so, for instance, once I had polished a silver snuffer, I learned that I needed to wash out the buffing cloth in a clothes washing area, hang the cloth to dry, and then replenish the cloth etc myself from a supply area provided for the children. This was deeply satisfying! Although most of us started by moving rapidly from one work to another, trying to see them all, within about 20 minutes, most folks had settled to a single work and had entered into deep concentration (flow?), almost as though entering into centering prayer.

In the adult area, Sherri had provided sequencing exercises which assisted us in learning to analyze the order in which pouring or polishing or spooning or nomenclature exercises should be introduced to the child. With regards to polishing exercises, for instance, glass polishing came first because of its solid, soap tablet; it was followed in succession by silver polishing which used a pudding like polish, wood polishing with its liquid polish, and finally brass polishing with its toxic liquid. Nomenclature exercises on the other hand began with first naming concrete objects (objects of the altar), then linking two-dimensional pictures of the objects with the objects, succeeded by linking written labels with the objects and then linking labels with the pictures, before finally moving on to three part and two part tray works leading the child to reading and writing the names of the objects independently on his own. Another areas sequenced pouring activities beginning with wrist development using dry pouring with small carafes filled with large objects such as popcorn, to carafes with small objects such as fine pasta or rice, and only then introducing dry pouring with pitchers which requires both wrist and finger coordination. An entire sequence of development from equal dry pouring with beans in carafes to a full preparation of the Eucharistic cruets with wine and water was outlined. I don’t know why this was so earth shattering; it’s so obvious once you see it. But I suddenly realized that an entire foundation for child development, allowing me to support a child’s success and joy with our liturgical pouring works, had been missing in my atria.

In addition, Sherri had provided hands-on materials which allowed us to explore the developmental needs of the 3- 6 aged child, to identify the characteristics of an environment which support normalization or which raise obstacles to normalization, to learn to recognize spontaneous concentration, and many other foundational elements of Montessori methodology.

A Catechesis of the Good Shepherd formation for adults wishing to work with children ages 3-6 always includes group discussions and presentations on Montessori methodology: “Who is the 3-6 Child?,” “What is the Role of the Adult?,” the “Theory of Practical Life,” etc. Since becoming a Level 1 formation leader, I have always followed these morning discussions with an afternoon adult lab for the level one formation participants like the one which Sherri and Marilee provided for me in Nashville.

At first the formation participants are impatient (“What does this have to do with my spiritual formation?,” you can hear them think), before something captures them, and they sink into contemplation of a work. Once they have been called into concentration on any one work, the entire atmosphere of the room changes to an experience of deep peace. As one participant said this last week here in Amarillo, “I wondered what pouring beans had to do with the Bible study I had been promised. But everything for the rest of the week built up from that moment. By the end of the week I knew that the preparation of the chalice rested on that child pouring the beans repeatedly for days and knowing the deep satisfaction and independence gained from that experience.”

I should say that I normally leave a couple of works in the lab incomplete on purpose, perhaps missing a tool of the work or the instructions for it or including the instructions but not providing any of the materials for a work. This allows the participants to experience the insecurity of a child being faced with a work which he does not know how to use, or finding a work he wants to do but not having the materials with which to do it. I do this for a sneaky purpose as will be discussed below.

After the participants have worked in the lab for two hours I quietly and privately invite each individual to take a break (bathroom, drinking fountain, etc) and ask them to come back in ten minutes. Then, like Sherri and Marilee, I remove the chairs from the work tables and form a circle with them for a group debriefing session.

When the participants come back into the room, many are upset! “I still wanted to work,” I’ve heard adults cry! So we talk about that. Based on this experience, what can we hypothesize about what it is that the child wants upon entering our atrium? To immediately sit in a circle and listen to an adult talk at them or to get to their work? This starts the ball rolling in a discussion about the rhythms of an atrium period, about the need for each material offered in the room to be complete, about how having someone hover over her shoulder inhibited the work of an individual participant, about the role of adult, about fostering the independence of the child, etc. This lasts for about 45 minutes and allows participants to deepen from their own experience the ideas of Montessori methodology that were hitherto only intellectual notes left within their minds from the morning’s discussions. What were simply abstract facts learned are now concrete experiences felt. It is, I think, quite powerful.

One caveat: I find that the adult exercises which lay out the model of Montessori’s thoughts about the normalization of the child can bring up powerful emotions in some participants. On rare occasions, a person who was abused as a child simply becomes overwhelmed by emotions when confronted with Montessori’s ideas abut normalization and has to leave the room. Likewise, occasionally, a parent projects upon herself or himself guilt for not allowing freedom of development for his or her own children. I am now prepared for these experiences, but I did not expect them when I first started including this lab.

I sincerely hope that the National Association of CGS hosts additional Montessori Essentials workshops in the future. The work of the adults and children in the atrium all benefit from our better understanding of the Montessori foundations upon which Sofia Cavalletti and Gianna Gobbi created their scriptural and Biblical works which so nourish the children in the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd.

The Covenant in My Coffee

Amidst the multitude of wedding gifts which my husband and I received was one I set aside as insignificant. There among the crystal, china, silver, and the linens – so exciting in their purity and sparkle – the small box with the two tear-shaped prisms seemed sadly out-of-place. Now that I think back, I don’t even remember seeing them set out on the tables of gifts displayed at the reception; perhaps my mother herself thought them too small to display to the public.

I remember receiving them though, sitting on the couch and oohing and wowing at each beautiful gift box I opened at that one shower. My husband’s maternal aunt had given them to me, offering her gift in her shaky hand as if the contents of her box were as precious as the rarest and most fragile jewel she possessed.

“These have meant the world to me,” she said as I opened her box. “I always thank God for them each morning as I drink my coffee. I don’t know how I would have found my way without them.”

Not really listening, I looked at the sad teardrops nestled in the yellowing cotton wool, and, already having dismissed them, already looking forward to the next gift, I murmured out some half-gracious reply and promptly forgot them.

* * *

Weeks later, after the honeymoon, I found them again while unpacking in my new home. I am sorry to say that I nearly carried them to the barn and put them away in storage, but some memory stirred in my mind of the wistful joy I had half-heard in the voice of P.J.’s aunt as she offered me these bits of her life. I washed them carefully, took a bit of twine, and – more to please my husband by honoring his aunt than for any other reason – hung them from the curtain rod above my kitchen sink.

And then I forgot about them again. You see, the window above my sink faced east, and I have never been an early riser. So I would come into the kitchen each morning long after the splendor of the morning sun had passed, and I would see only two chunks of oddly cut glass which gathered dust hanging in front of my window. I wondered occasionally why they had been so special to my husband’s aunt. Had they been gifts from her husband? From a child? Or perhaps from a childhood sweetheart?

* * *

After our son was born, it became a tradition of mine to read morning prayer to him as he ate his morning cereal. Belted in his high chair, he was a captive audience, and he responded to this attention with coos of delight. As he grew older, outgrowing his high chair and his belt altogether, he outgrew this morning ritual too. By the time he turned two, I had stopped including him in my reading for the simple fact that he had finished his breakfast and gone to his toy box before I would have even finished the reading of a psalm. Even then, I began to anticipate having another child with whom I could resume this morning ritual. Little did I know then that my son’s ability to sleep in with me in the morning was an anomaly; not all infants are born as owls who sleep more deeply as the sun begins to rise.

My second child took after her father and chose to be a lark. Up at the slightest crack of dawn, she was impatient to get after everything the new day had to offer. I don’t remember ever drinking coffee in the morning before Lauren was born; I couldn’t have survived the mornings after her birth without it. Groggy and still half-asleep, I would carry her to her high chair in the dim half-light of pre-dawn, hang unsteadily to the handle of the microwave until her bottle and cereal was ready, and then slump into my chair with a comforting cup of warm, milky coffee in my hand. Yet even in those painfully early hours, I hoped to recapture those joyful prayer sessions with my daughter, and when the warm caffeine began to flow through my veins, I would open my prayer book and try to begin.

Oh, alas, for young parents who expect all of their children to be alike!

Where my son had been attentive, my daughter was restless. Where my son had been welcoming and malleable, my daughter was fiercely independent and well set in her opinions by the age of three months. Where my son had had the attention span of a well-intentioned adult, my daughter was frankly disinterested within a matter of minutes. So much for recapturing the joy of communal prayer in the pre-dawn hours! As she fussed, I became more frustrated.

Then one spring morning, angrily giving up on yet another frustrating attempt to read even the opening collect of the office, I heard her coo with delight. Looking up, I saw her reaching for my coffee mug with a look of joy and fascination. There on my mug, covering my mug, dancing even in its interior rim, were rainbows. The morning sun had pierced the window over my sink, and shining through the two dull prisms hanging there had made my coffee, my kitchen into a wonderland.

We shared that morning simply the joy of the rainbows. I would chase them for her or make them dance madly by spinning the crystals in the window. She would laugh in peals of glorious, musical laughter at the swirling colors around her. Those rainbows brought us together as nothing in the months prior had, and as the rainbows in my coffee became a morning ritual for us, we learned to love each other more each day.

I would like to say that on that first morning I had a revelation about the prisms, but that would be untrue. Over the years, as I sipped my milky coffee or made the prisms dance in the sunlight for my daughter, I thought about them, and only slowly did I come to understand what they mean to me and what a gift I was given on that long ago wedding day.

Those rainbows helped me understand the relationship I had not only with my daughter, but also my son, my husband, and all of the members of the community of God who I encounter in my journey through creation.

I came to understand that I was wrong to look to my daughter to be the reproduction of her brother or the replica of myself. We were all of us, different as we were, like three adjacent facets on one of those prisms. We thought we knew clearly where our boundaries lay, where she or he or I began and ended, yet we did not know the greater things. We had forgotten that we were not the maker of the prism, nor the source of the light which shone through us.

Long before our awareness even began, greater hands had taken a clump of wet sand and subjected the mud to so intense a fire that the sand was purified into crystal clarity. Loving, unknown hands had carved this crystal to a design that only the maker fully understood, shaping each facet to reflect its own and individual beauty and binding each facet to its neighbors to create a greater beauty than any facet could present on its own. A powerful and joyful light shone though us, giving us the ability to each, in our own way and in our own turn, release a small part of the great spectrum of that light into the world around us.

It is an uncomfortable fact of life that as we grow older we can no longer sleep in as we did when we were younger. My bed no longer feels as comfortable to my fifty-year old arthritic body as it did when I was twenty, and so most mornings for several years now, I have been up and watching the rainbows in my coffee. On most of those mornings, I see in my coffee those colorful reminders of the covenant of love which binds all of us in creation. I believe that this daily reminder of God’s love for me, of my relationship to his other creatures and my fellow men, and of the precious gifts which he gives each of us to share with the world, has helped me be more loving and patient whenever trouble or discord has developed in my relationships.

I think now, on my daughter’s distant wedding day, I will take these crystals down from my window and carefully pack them in cotton wool in a beautifully wrapped box. And then I will offer them to her as though they were the most rare and precious jewels I possess. “Take them,” I will say. “These have meant the world to me; I always thank God for them each morning as I drink my coffee. I don’t know how I would have found my way without them.”

I hope she will find the message in them that I found, and that she will be as grateful some day as I am now when I remember that dear, wonderful aunt of my husband’s whose hand shook as she offered her greatest gift to me.

The Sweetness of the Shepherd

My atria are set up for combined levels at the school. This means that the “little school” room is set up as a Level 1 and Level 2 combined atrium and that the “big school” room is set up for Level 2 and Level 3 to share. Occasionally, I worry, because I see the older children return over and over to works created for the younger. I question whether the child is really exploring something new in the younger work or simply trying to escape from engaging in real work. Here, I am often saved in the midst of my anxiety, by the words of those giants who came before me: Maria Montessori, Sofia Cavalletti, and Gianna Gobbi.

When seeing an older child return over and over to the work with the sheepfold, the Good Shepherd, and the sheep, I have learned to follow Montessori’s admonition to “wait observe”. Watching closely the child’s work, it is often simple to see that the child truly IS involved in the scriptures of John 10 or Luke 15 in a deep and meaningful way, and when I need verification for myself that their work reveals that the Word abides in the child, I can always turn to the children’s work journals.

Earlier this week, two third grade girls spent the entire atrium time working over and over with the Shepherd and the sheep. Their movements were careful and meaningful, their voices soft. Watching them, I saw frequent long pauses where the two of them simply sat in contentment by the work, gazing into the heart of the sheepfold or caressing the shepherd figure with their eyes. Occasionally, one would reach out to stroke or pat one of the sheep.

Later, after they left the room, I sat to read through the group’s work journals in order to make notes for myself for their next visit to the atrium. Here I found in the journals of these two girls their growing relationship with Christ.

One girl concentrated on the idea of the Good Shepherd himself, his sacrifice, his Eucharistic presence, and his abiding love:

“I think that the sheep are the people and the good shepherd loves them so much he will sacrifice himself for us. I think that is very sweet. Jesus will lead us to food and he will love us forever. I think that he was very nice for giving the bread and the wine to us. I will always remember him.”

So much to see in this one short paragraph! Here is sacrifice presented not as suffering but as a gift of love, as an act which brings forth sweetness. Here is a response of anamnesis to Christ’s request to “remember” him in the bread and wine of Eucharist. Here is the knowledge that Christ calls us to himself and gives us all himself in the consecrated bread. Here the child responds to the call of Christ.